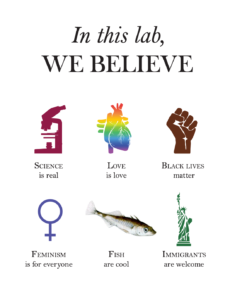

The lab recognizes that there is a problem with discrimination, inequity and exclusion in our society. We aim to create a welcoming lab environment that acknowledges the toll these disadvantages take on mental health in both work and non-work settings. We think that science is better (and more fun!) when it includes diverse perspectives, that we need to take active measures to support and promote them, and that we need to continually revisit this commitment and look for ways to improve it.

In addition to this commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion, here are other lab values:

1) We help each other succeed.

2) Communication is key! We communicate as a group to coordinate activities, as well as to help each other. Lab members are expected to check their email or Slack at least every 24 hours as that is our primary method for staying in touch, and to always reply to emails that are personally directed to them, even if only to say “OK!” or “I’m looking forward to reading this next week” or “Got it!”. Alison meets with members of the lab regularly. Once a week tends to be good during the early and late stages of a project/PhD, with less frequent meetings in the middle of a project when data collection is in high gear. Alison is always happy to meet with you. Please send Alison material to read/think about BEFORE we meet rather than during the meeting so she has a chance to think about it. We use a Google calendar to keep track of lab meetings, fish feeding duties, etc and we write when we will be away on the lab calendar so we can plan accordingly. We use Slack to coordinate and disseminate information for the lab, and we use Box to store data, protocols, videos, etc.

3) We strive to do integrative research. A good goal is to try to address at least two of Tinbergen’s Four Questions over the course of a PhD.

4) We study a fabulous supermodel organism. Here are two specific suggested activities to fully take advantage of the strengths of stickleback: (1) read the classic ethological literature; (2) go to the stickleback meetings at least once during a tenure in the lab; the stickleback meeting can be a great crash course on all things stickleback.

5) We believe in publishing our findings. The problem is that writing papers is hard. One way to make it easier is to receive feedback at every stage of writing a manuscript and to break down the steps of preparing a manuscript into smaller and more do-able chunks, and set a timeline for completing all of the steps. Starting a paper can feel paralyzing, and one way to lower the barrier to entry is by starting with the easiest part of the paper: the Methods section. Once there is a draft of the Methods section, send it to Alison for feedback. Ideally this will happen before data collection begins in earnest. Next comes Results. Lab members are encouraged to share figures/stats before a meeting, then we can discuss them and think about the best ways of visualizing the data, the most appropriate ways to analyze and interpret them and ultimately settle on the final figures and tables to go in the paper. Then, send Alison a draft of the Methods + Results (which incorporates comments on the methods). Intro and Discussion typically come last, either together or Introduction first. Again, by exchanging drafts at each step of the process there is an opportunity to get feedback on all of the previously-written sections before moving on to the next one, and to incorporate feedback on the MS as a whole as it begins to take shape. Sometimes there may be suggestions that lab members don’t agree with – that’s fine! The track changes function in MS Word is a great venue for responding to one another’s Comments in writing. Of course ultimately it’s best to discuss points of contention in person but the Comments section can be a good way to get the ball rolling on paper.

6) Good time management helps. Doing science takes a long time so it’s important to plan accordingly. Experiments usually take at least three times as long as anticipated. Data analysis and writing are even worse; they will probably take at least five times longer than planned. Procrastination is a slippery slope and it’s great when we can structure our working environment to avoid working at the very last minute as much as possible. Alison is committed to getting feedback to you and to help you in as expedient and efficient a manner as possible; in exchange lab members are encouraged to follow through on self-imposed deadlines and not wait until the last minute to send things for feedback. Help will be a lot more effective if we have time to work through it together! A great task to save for the very end is triple checking the formatting of the reference list.

7) We meet for lab meeting. All members of the lab are expected to attend and participate in lab meeting. Lab members sign up to lead a lab meeting at least once a semester. Leading a lab meeting might involve activities such as the following: showing and discussing recent results, leading the discussion of a published paper, brainstorming about how to design an experiment, practicing a talk, asking for feedback on a MS or grant application, etc. If we are reading something for lab meeting, the leader is expected to share the material so there is enough time for us to read it before we meet. We plan ahead – if a lab member knows they have a deadline, they reserve a spot for lab meeting at least two weeks before the deadline.

8) We value the welfare of animals in our care. Many of us are studying animal behavior is because we love animals. We work with live, often wild, animals. We don’t forget that it is a privilege to work with live animals, and it is our moral – and legal – responsibility to consider the welfare of the animals in our care. It is also our responsibility to make sure that each of their lives contributes to scientific understanding. What this means: we treat our animal subjects responsibly and ethically, obtain all necessary permits for collection and study of animals in the wild and in captivity, maximize the quality and amount of data collected on each individual subject and publish our results so the scientific community can benefit from our studies. We allow ourselves plenty of time to apply for necessary permits (collection, import/export, etc) to carry out our research. Lab members read and are familiar with our Animal Care and Use protocol, and keep it up to date and accurate.

9) We collect high quality behavior data. We do a lot of behavior experiments in the lab, and often rely on multiple observers for collecting behavior data. Luckily, there are good methods for assessing both inter- and intraobserver reliability of our behavior data recording methods. Before starting to collect data, we make sure that reliability is good (>90%) both within and among observers. Once data collection is underway, we keep close tabs on anyone collecting data for us, and check their work periodically to be sure that all of the people involved are being consistent. We back up our data!!!!!

10) We seek and value constructive feedback. At the end of the academic school year, we complete an evaluation. First, lab members complete a self-evaluation (typically provided by the graduate or other advisory program). Alison reads the self-evaluation, offers feedback, and offers her own evaluation. Then we meet to talk about it. The best question is what do YOU think will be your biggest challenge over the next year, and what are things that Alison can do to help you over the next year. We communicate about what have been our challenges with independent research to date – we reflect on what we think is our Achilles’ heel/rate limiting step/barrier to progress. This could be, for example, perfectionism, time management, procrastination, imposter syndrome. It helps to know what lab members think are going to be challenges so that we can discuss ways of dealing with them together, so Alison can be on the lookout for ways that to help.

11) We are good lab citizens. We close the doors and turn off the lights when we are the last to leave the lab. We are aware of theft (especially at the beginning and end of the semester) and do not leave valuables (laptops, videocameras) visible on the countertops. Lab members view the lab as THEIR lab and take responsibility for it. If someone breaks something, they fix it. We always clean up every tool that we use as well as the lab bench. If someone uses the last of some supply or notices that the supply is running low, they order more, or let the lab manager know so that they can order more (it takes time to replace things!). If something needs to be improved, we suggest an alternative. If someone moves something, they put it back. We don’t steal sharpies! We throw away pens that don’t work. If we have a cool idea, we share it. We keep the protocols up to date on the Bell lab folder on Box. If we develop a new procedure, we make a protocol to share it with the lab. We keep solutions clearly labeled with what it is, date it was prepared, who made it and we replace them often. We clean up our space when we leave the lab, dispose of all solutions. If we’re not sure how to dispose of a solution, we ask the lab manager.

We all take turns feeding the fish and expect everyone to do a good job — we treat all the animals as though they are our precious experimental subjects. We record our initials and time on the clipboard. We dispose of dead fish immediately. We don’t leave dead fish in the food freezer. If we see something funny or unusual in one of the tanks, we tell someone (ideally the person responsible for those fish). If we are keeping fish in the fish room it is our responsibility to let the fish feeder know the requirements for our animals, i.e. extra food, no food, special food, etc. It is our responsibility to make sure that the fish count is accurate on the tank card and that visibility is clear so that the fish feeder and DAR can assess fish health/numbers. We put dead fish label on tanks with dead fish even when we are not feeding and inform the person responsible for those fish that there has been a death. We never fill tanks with water from the sink. We recycle as much sand and gravel as possible and don’t let it go down the drain. We return things to their original place if we borrowed them. We make sure over-tank lights are off in 43 when we leave (they are not on the timer system).

12) We help others succeed by writing letters of recommendation. In order for a letter writer to write you the strongest possible letter, we provide them with the following information at least TWO WEEKS before the application is due. What is the name of the fellowship/award/grant we are applying for? When is it due? Is that postmarked date or due date? To whom should the letter be addressed (name and address)? What should the letter writer do with the letter once it’s written? Does the letter writer print out a hard copy, sign it and put it in a signed and sealed envelope? Do they put the envelope in the mail or give it to you? Is it submitted online? Is the application meant to emphasize something particular, e.g. community service, advancement of women and people from under-represented groups, etc? We provide a copy of the application, including the most recent CV and whatever statements are required. Whenever possible, we provide the name and title of the person who will receive the completed letter. “To whom it may concern” sounds generic, and inappropriate use of Miss, Mrs, Ms, Mr, and Dr can be offensive. A letter writer always likes to know why he or she is being asked, so we provide this information if we can. We also communicate the names of other letter-writers; this information helps the letter writer adjust their comments in important ways, e.g. because you attended the letter writer’s office hours and our conversations during office hours influenced your thinking, or because the letter writer is a member of a society and you are applying for a grant from that society, or because the letter writer is an alum of a particular university and you are applying to attend that university, etc.

13) We love graduate students! PhD students in the lab typically take 5-6 years to complete their degree. Students might need a 6th year if something goes wrong, funding allows, or if there is something super cool to pursue. Graduate programs typically expect students to submit >3 manuscripts for publication in 5 years. We know that publishing is much harder and takes much longer than we think it will (or should). Everything (exams, completing projects, securing a postdoc, etc.) is easier if we publish soon and publish often. Not sure what to do? Collecting data, reading and writing are always good. If we are not collecting data, we try to read and write every day. We present at a local venue (e.g. GEEB symposium, Neuroscience SfN poster night, IGB theme hop) at least once. We apply for SIB and external grants every year. Public outreach and science communication is encouraged! We participate in reading groups and seminars and are encouraged to consider co-writing a review paper. Graduate students TA > 2x. If students are aiming for a career in teaching, they are encouraged to pursue opportunities available through, for example, the Center for Teaching Excellence. However, we keep in mind that the primary goal of graduate school is to learn how to do high quality research, and that experience has many transferrable benefits (e.g. learning how start and complete a multi-year project, how to communicate, how to work with others, how to learn and implement new technical skills, etc). Also, it is difficult for PhD students to get a teaching job if they don’t do the research required for a PhD. We go to a national or international conference ~1x/year. Members of the lab regularly attend conferences such as ABS, ISBE, SfN, SICB, Evolution, Am Nat, Gordon Conferences, SBN, ISNI and IBANGS. Graduate students meet with their committee meeting 1x/year and meet individually with their committee members 1x/year (more is better).

A typical timeline for PhD students in the lab:

Year 1: Tinkering – fish, lab work, learn from others in the lab; Apply for NSF predoc and other fellowships; Take classes – stats, programming, genomics and any coursework deficiencies; Summer – first field season, get lots of data, explore; Meet with committee.

Year 2: Collect data; Analyze data, plan next experiment; Apply for grants and fellowships; Prep for prelim; Write Chapter 1; Take prelim if Chapter 1 submitted; Become involved in outreach; Fill in any remaining coursework deficiencies; Meet with committee.

Year 3: Collect data; Submit Chapter 2; Reflect on career goals; Meet with committee.

Year 4: In the zone of data collection – this is the year when students usually get the most done; Apply for Dissertation Completion Fellowships; Consider postdocs/the next step; Meet with committee.

Year 5: Apply for postdocs/jobs; Write Chapter 3, defend.

14) We make our data publicly available. We deposit our data on depositories such as Dryad and GEO upon submission and/or publication. We keep good records of unpublished data (including annotation files defining variable names, linked methods, etc) and store the data on Box; we store large files of genomic data on an archive through the IGB.